Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) can send you into a kind of split-screen reality. There’s the “you” you remember; the one with preferences, humour, rhythms, instincts. And then there’s the version of you that OCD throws into the foreground: hyper-vigilant, terrified of your own mind, exhausted from trying to outrun thoughts you never asked for.

Many people with OCD say the same thing: “I don’t feel like myself anymore.” The sense of becoming a different person doesn’t come from weakness or instability. It comes from a disorder that distorts threat, identity, and meaning until everything feels unfamiliar. This article explores why that happens, why it feels so convincing, and how people reconnect with themselves as symptoms ease.

Key Takeaways

- OCD can distort your self-perception.

- Intrusive thoughts can make you wonder what it says about you to have such a thought.

- Specific OCD subtypes, like Sexual Orientation OCD or Relationship OCD, directly target a person’s sense of identity.

- Shame and withdrawal from intrusive thoughts can reinforce a sense of becoming someone else.

- Treatment for OCD aims to help shift the sense of becoming someone else by reconnecting you with your core self.

The Identity Disruption That OCD Creates

One of OCD’s most destabilising effects is the fracture it creates between who you are and what your mind produces. Intrusive thoughts often clash with a person’s deepest values; for instance, a gentle person receives violent mental images, a loving parent experiences repulsive or inappropriate thoughts, and a spiritual person may encounter blasphemous impulses.

This clash is called an egodystonic experience: the thought feels wrong, foreign, “not me.” Yet the mere fact that the thought happened makes the person wonder whether it reveals something dark within them. That moment, the instant OCD links the thought to identity, is often where the sense of being a different person begins.

People describe feeling alienated from their own preferences, emotions, sense of goodness, or moral compass. They question their ability to trust themselves. They may even tell a before-and-after line: “I know who I was before OCD, but I don’t know who I am now.” OCD doesn’t replace a person’s identity, but it can cloud it so entirely that the true self feels unreachable.

The Shock of Intrusive Thoughts That Don’t Match Your Values

Intrusive thoughts are a universal experience; almost everyone encounters them. But OCD attaches significance to these flashes and turns them into evidence of a possible hidden self.

A single disturbing thought can feel like a revelation, and is often followed by questions like: “What if this means something bad?” or “What if I’m dangerous?” or “What if I’m immoral?” or “What if this thought exposes the real me?”

People with OCD often describe the thoughts as so vivid and emotionally charged that they feel like impulses or memories rather than meaningless mental noise. The intensity of the fear makes the thought feel real, even if it directly contradicts the person’s identity.

Over time, the brain forms a loop: Intrusive thought → panic → compulsive mental checking → temporary relief → new intrusive thought. This cycle conditions the person to treat each thought as a threat. And when the danger is about identity, the result is a constant feeling of disorientation. The person doesn’t actually become someone different, but they start living as if the feared identity is waiting just outside their field of vision.

Subtypes of OCD That Directly Target Identity

Some OCD subtypes make a person more likely to experience a sense of their identity being attacked than others. These include:

- Harm OCD: People fear causing harm to loved ones or strangers, despite being deeply gentle and conscientious. They may interpret the fear itself as proof that they’re dangerous.

- Sexual Orientation OCD (SO-OCD): This subtype triggers obsessive doubt about sexual orientation, even when a person has lived for years with clarity about their attractions. The distress isn’t any particular orientation itself, but about their resulting preoccupation with gaining clarity around it.

- Relationship OCD (ROCD): Here, identity disruption appears in doubts about whether someone truly loves their partner or whether their partner is “right.” The person may feel disconnected from their own emotions or instincts.

- Pedophilia OCD (POCD): This is one of the most traumatising subtypes, creating a terrifying fear of being attracted to children despite the person’s values and history showing the opposite.

These subtypes don’t reveal new truths about a person. They hijack their most cherished parts, including empathy, honesty, and morality, and turn them into vulnerabilities.

Emotional Fallout: Shame, Fear, and Withdrawal

When OCD targets identity, the emotional consequences run deep. People often report feeling ashamed of their own minds, even though the thoughts are unwanted. They may fear being judged, exposed, or misunderstood, which leads many to withdraw from relationships or silence themselves socially.

A person who once felt warm, spontaneous, or expressive may start to appear rigid, cautious, or distant. Loved ones sometimes notice the change and don’t know how to interpret it. The person with OCD may feel trapped inside a mind that no longer feels inhabitable. This withdrawal reinforces the sense of becoming someone else. The more a person disconnects from the world, the more convincingly OCD whispers: “This is who you are now.”

Cognitive Distortions That Twist Self-Perception

OCD amplifies specific thinking patterns that distort a person’s relationship with themselves:

- Catastrophic interpretation: A single intrusive thought becomes a sign of future danger or moral collapse.

- Overresponsibility: The person believes they must control every thought, impulse, or mental image to prove they’re safe.

- Moral perfectionism: Any deviation from perfect internal purity feels like a character flaw.

- Black-and-white self-assessment: One thought or feeling threatens to redefine the person entirely.

These distortions make ordinary mental events feel like identity-shifting crises.

The Sense of Two Selves Inside One Mind

Many describe OCD as feeling like another presence or voice — not a hallucination, but a constant mental commentator. There’s the rational mind, which knows the thought is irrational, and the OCD mind, which interrogates, doubts, and demands certainty.

The internal tug-of-war creates a sense of detachment, with thoughts like: “I know who I should feel like, but I can’t access that version of myself” or “I’m watching myself act like someone I don’t recognise.”

This experience can resemble depersonalisation; a sense of watching yourself from outside your body, or feeling emotionally distant from your own life. When intrusive thoughts cluster at the centre of this, the person feels trapped in a distorted self-portrait drawn by their own fear rather than reality.

The Pressure to Hide the “OCD Version” of Yourself

Because intrusive thoughts are taboo, violent, sexual, or morally charged, many people hide their symptoms. That secrecy reinforces internal division: the “public self” who must appear stable, and the “OCD self” who wrestles with agonising doubts.

This splitting can feel like living in two incompatible identities. The longer symptoms remain hidden, the more the person feels cut off from any sense of wholeness.

What Recovery Looks Like: Reclaiming Yourself From OCD

An encouragingly common report from people in treatment for OCD is that when symptoms shift, the authentic self comes back into view. Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP), a gold-standard treatment for OCD, helps people stop responding to intrusive thoughts as threats. As mental rituals decrease, the thoughts lose their intensity and authority.

The person gradually realises, “The thought wasn’t me” or “My values never disappeared, they were just buried under panic.” The therapy that supports these realisations also helps rebuild inner trust. Instead of checking for certainty, the person learns to move forward without answering every identity-based question. Over time, this calms the nervous system enough for the person’s natural personality to resurface.

Starting to Feel Like Yourself Again

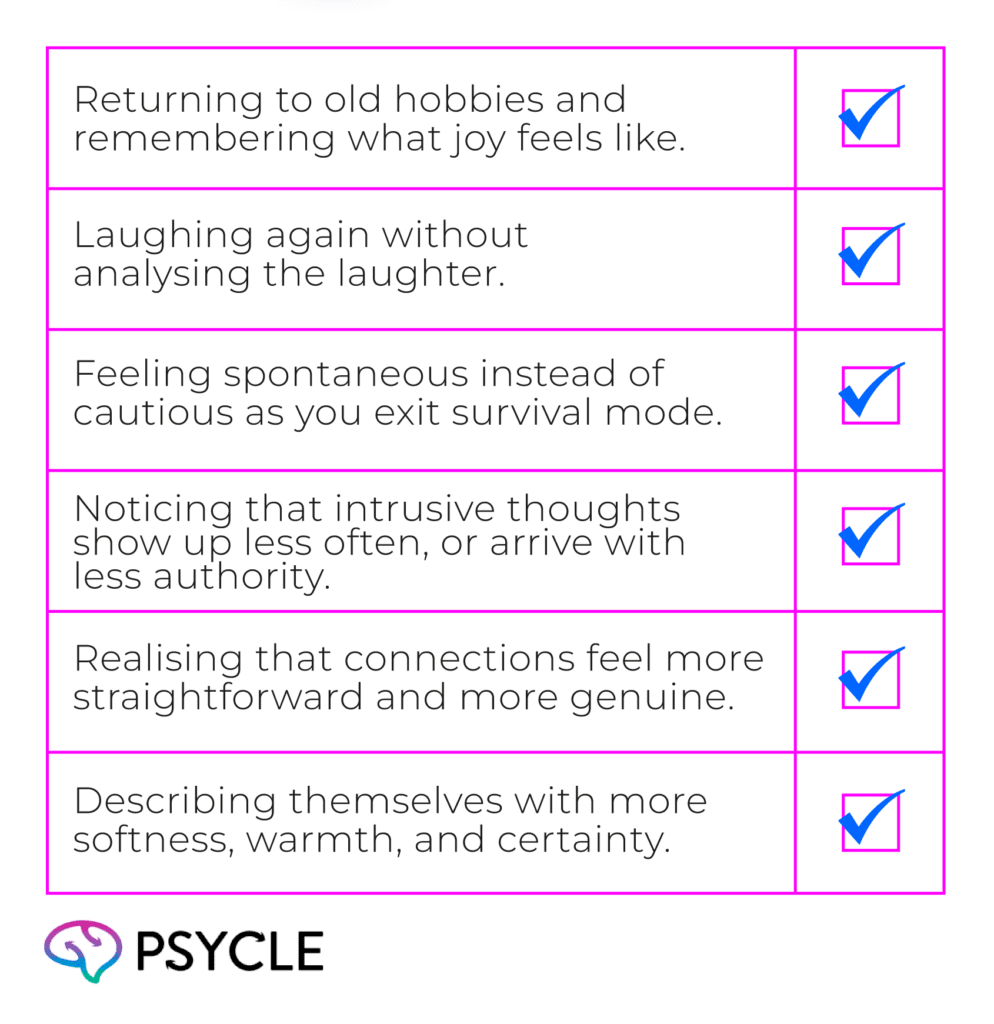

Recovery doesn’t require discovering a “new” identity. It requires removing the noise that has been drowning out the existing one. People often describe:

These shifts are most likely to be noticed gradually over time, as treatment for OCD continues.

Why You Are Not a Different Person, Even If It Feels That Way

OCD does not alter core identity, but it can obscure access to it: People with OCD do not become dangerous, immoral, confused, or empty, but they do, understandably, become anxious. As a knock-on effect, anxiety shifts behavior, emotion, and cognition. So what may feel like a personality change is actually a person with OCD’s adaptive responses to perceived threats.

When symptoms of OCD ease, many people describe the same realisation: “I didn’t become a different person. My sense of self was intact; I just couldn’t reach it.” OCD disrupts your experience of identity, but it cannot and does not determine who you really are.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can OCD Permanently Change My Personality?

No. OCD can cover your sense of self, but recovery consistently reveals that your underlying personality remains intact.

Why Do Intrusive Thoughts Feel Like They Reflect Who I Am?

Because OCD misinterprets intrusive thoughts as threats, your body reacts with fear. The fear makes the thought feel meaningful even when it isn’t.

How Do I Begin to Feel Like Myself Again?

Seek treatment, such as Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP), to reduce compulsive responses, engage in values-led activities, and gradually allow your real preferences and instincts to re-emerge.

Sources

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9129584/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10084853/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4252512/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prnN0nZONcI

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1353962/full

- https://www.michiganmedicine.org/health-lab/stuck-loop-wrongness-brain-study-shows-roots-ocd

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28822003/

- https://adaa.org/learn-from-us/from-the-experts/blog-posts/consumer/overcoming-harm-ocd

- https://lightonanxiety.com/conditions/sexual-orientation-ocd/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/social-instincts/202109/ocd-and-perceived-catastrophe

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8650182/

- https://www.academia.edu/13580137/The_characteristics_of_unacceptable_taboo_thoughts_in_obsessive_compulsive_disorder

- https://www.uwlax.edu/globalassets/offices-services/urc/jur-online/pdf/2021/werner.lily.cst.pdf

- https://www.ocduk.org/overcoming-ocd/accessing-ocd-treatment/exposure-response-prevention/